The Art of Seeing Through: Why Clarity Is a Skill, Not a Mystery

Clarity isn’t something you wait for. It’s a perceptual skill you develop—the ability to see what a situation is actually about beneath the noise.

Most people think clarity arrives as a moment.

A sudden sense of certainty that resolves everything effortlessly and wondrously, so that your months of angst are lifted and you're left feeling clear, grounded, and at peace.

We love narrating it this way afterward: "I just knew." "It hit me all at once."

Here's what that story leaves out.

Clarity is the ability to see what a situation is actually about—not what it appears to be about, not what you wish it were about, but what's really happening beneath the surface.

What clarity is not:

- A sudden breakthrough that arrives unannounced

- Intuition reserved for people with better instincts than you

- Something you sit around waiting for

- More information or deeper analysis

What clarity actually is:

- A perceptual skill you develop through practice

- The ability to read signals beneath noise

- Seeing through, not just looking at

- A way of observing that reveals what matters

Some people simply learned it earlier than others.

Why Clarity Feels Elusive Now

We live in an era of unprecedented information and unprecedented confusion.

More options, more opinions, more frameworks, more advice than ever before. And yet many intelligent, thoughtful people feel increasingly unsure—about their work, their direction, their next move.

This isn't because they lack intelligence.

It's because they're overwhelmed. The signal-to-noise ratio has become impossible.

We've been taught to think our way to clarity: make a pro/con list, analyze harder, gather more data, ask more people.

But clarity rarely comes from accumulation.

It comes from discernment—the ability to see what matters and what something is actually about beneath all the noise.

That ability isn't mysterious. It's perceptual.

Seeing Through vs. Looking At

There's a difference between looking at something and seeing through it.

Looking at stays on the surface: the stated problem, the visible facts, the official story.

Seeing through goes deeper: the underlying pattern, the cultural context, the hidden assumption, the quiet signal that explains everything else.

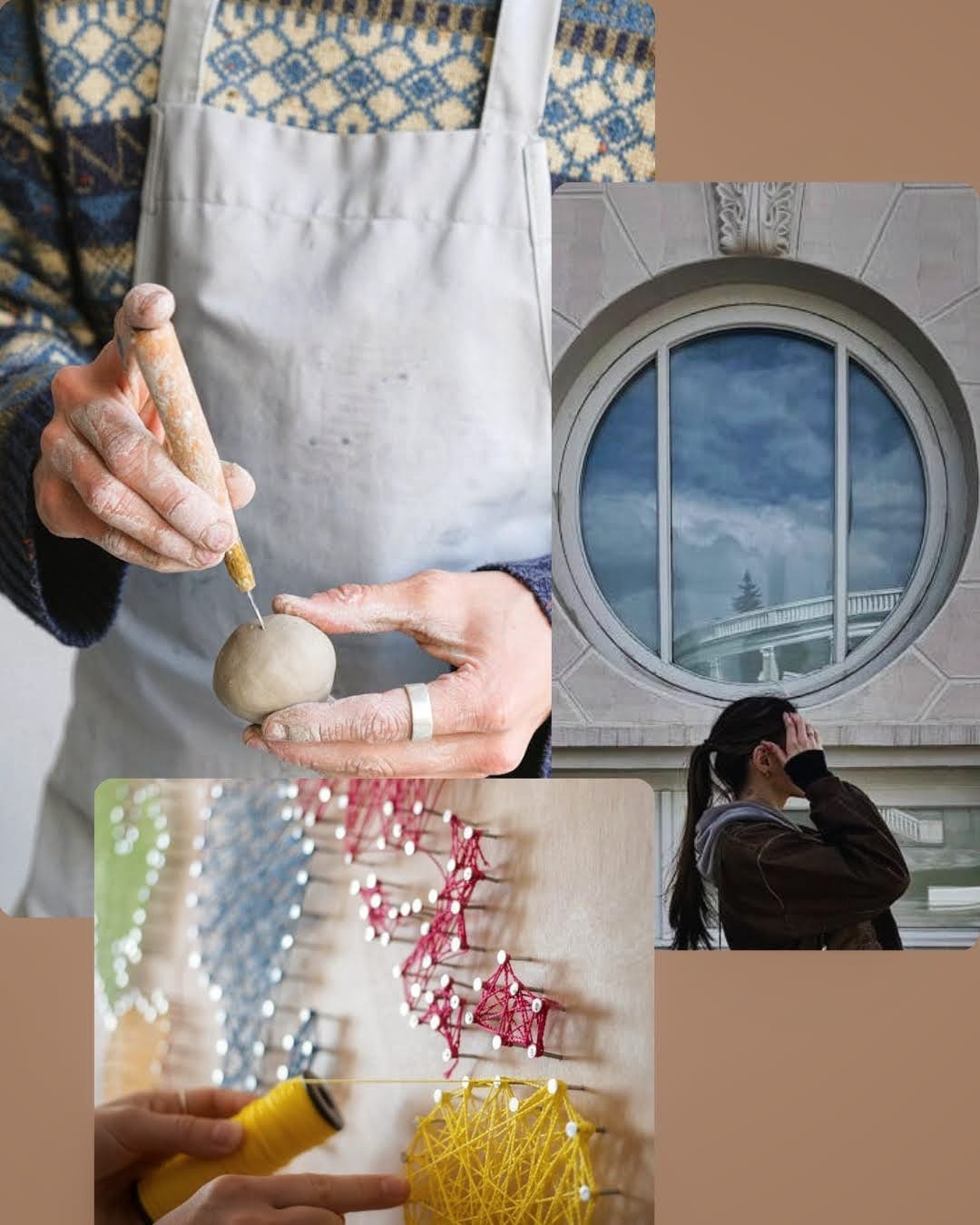

Journalists understand this instinctively. So do curators, designers, editors, and craftspeople.

They don't just ask what is this? They ask why does this exist this way? What does it reveal about the system that produced it? What doesn't quite add up?

This is the same perceptual skill that creates clarity in life decisions.

The art of seeing through applies everywhere—to objects, to culture, to relationships, to work, to the moments when you need decision clarity most.

The Three Lenses of Seeing Through

Clarity isn't a feeling. It's a process.

Specifically, it's the practice of looking at any situation—a museum object, a career decision, a relationship crossroads—through three distinct lenses.

These are the same lenses journalists and curators use to read the world.

The Maker's Eye: What Choices Were Made Here, and Why?

This lens notices craft, intention, and constraint.

It asks: What was chosen? What was rejected? Where did care get applied? Where did something break down?

In a ceramic bowl: the thickness of the rim, the balance of glaze, whether speed or patience guided the process.

In your life situation: What choices led here? What's been prioritized? What's been compromised? Where is effort being applied, and where is it being withheld?

This lens reveals agency—yours and others'. It shows you what's been constructed, and how.

When you develop the Maker's Eye, you stop asking "why is this happening to me?" and start asking "what's actually been built here?"

That shift alone restores clarity.

The Context Eye: What Larger Forces Shaped This Moment?

This lens reads systems, history, and power.

It asks: What cultural moment produced this? What incentives are operating? What's the larger pattern this belongs to?

In a museum: Why does this object exist? What does it reveal about the society that made it? Why is it here, in this collection, now?

In a career crossroads: What industry forces are shifting? What generational expectations are you carrying? What's the water you're swimming in that you can't see?

This lens stops you from taking things personally that are actually structural.

The Context Eye creates clarity by showing you what's yours to change and what's simply the landscape you're navigating.

Most confusion dissolves when you can see the difference.

The Personal Eye: What Does This Reveal About How You See?

This lens turns perception back on itself.

It asks: What am I responding to? What's capturing my attention? What am I avoiding noticing?

In an artwork: Why does this move me? What does my reaction reveal about my own values, my aesthetic formation, my current state?

In a decision point: What keeps surfacing? What feels heavy versus light? What am I drawn to despite logic? What story am I telling myself about what's possible?

This is where observation becomes insight. Where pattern recognition becomes personal wisdom.

The Personal Eye doesn't ask what you should do. It asks what you're already seeing—and what that reveals about what matters to you now.

When to Use The Three Lenses

The art of seeing through applies everywhere—to objects, to culture, to the moments when you need decision clarity most.

Career crossroads: Should I stay in this role or leave? What am I actually building here? What larger industry forces am I navigating? What does my restlessness reveal about what I need now?

Relationship decisions: What's been constructed in this dynamic? What cultural or generational patterns are we repeating? What does my response tell me about what I value?

Creative or professional blocks: Where has effort been applied and where has it been withheld? What's the larger context that's shaping this moment? What keeps surfacing in my thinking despite logic?

Life transitions: What choices led here? What's mine to change and what's simply the landscape I'm navigating? What feels aligned versus misaligned?

The Three Lenses work the same way whether you're reading a ceramic bowl or reading your own situation. The method doesn't change. Only the subject does.

When These Three Lenses Work Together

Clarity emerges when you can hold all three perspectives at once.

The Maker's Eye shows you what's been constructed. The Context Eye shows you why it was constructed this way. The Personal Eye shows you what it means for you.

This is how journalists read a story beneath a story. How curators understand what an object is saying. How anyone with practiced perception navigates complex situations.

It's not about having more information. It's about developing the capacity to see through what's in front of you.

Why Smart People Struggle with Clarity

Ironically, intelligence can make clarity harder.

Highly capable people often over-intellectualize emotional signals, override intuition with logic, absorb too many external perspectives, or stay inside narratives that no longer fit.

They're skilled at thinking, but not always at seeing.

Clarity breaks down when the mind is too loud, the signal-to-noise ratio collapses, or external frameworks drown out internal coherence.

This is why clarity often returns during moments of enforced stillness: travel, illness, grief, transitions.

The noise drops. The signals remain.

The question isn't whether the signals exist. The question is whether you've developed the perception skill to read them.

A Small Case Study in Seeing Through

Consider a simple object: a ceramic bowl.

At first glance, it's just a bowl.

But when you apply the three lenses, something shifts:

The Maker's Eye notices the weight distribution, the thickness of the rim, how the piece sits in your hand. These reveal the maker's experience level, their relationship to material, whether speed or care guided the process.

The Context Eye asks: Is this a production piece or studio work? What tradition does the glaze technique come from? What does the form tell you about how people ate in that culture?

The Personal Eye observes your own response: What draws you to this bowl? What does it remind you of? Why does this object, among all the bowls in the world, hold your attention?

Now apply the same method to a life situation.

The Maker's Eye: What choices created this situation? Where has effort been applied? What's been built, and how?

The Context Eye: What larger forces are shaping this moment? What's the industry doing? What's the culture expecting?

The Personal Eye: What keeps surfacing in your thinking? What feels aligned versus misaligned? What are you drawn to despite yourself?

The bowl doesn't lie. Neither does your life.

You just need to develop the capacity to read it.

Why Clarity Is Often Mistaken for Confidence

We tend to admire people who appear decisive.

But decisiveness is not the same as clarity.

Some people decide quickly because they ignore signals. Others decide slowly because they're learning to read them.

True clarity has a different texture.

It feels grounded, proportionate, calm rather than euphoric, quietly inevitable.

When clarity arrives, urgency fades. You stop forcing movement. You know where the weight belongs.

This is the difference between decision clarity and decision speed. Speed might feel productive. Clarity actually is.

A Simple Practice to Develop Clarity

You don't need a dramatic life change to begin practicing the art of seeing through.

Try this instead:

The One-Layer-Deeper Exercise

Choose one situation that feels unresolved.

Apply the three lenses:

The Maker's Eye: What's been constructed here? What choices created this? The Context Eye: What larger pattern does this belong to? The Personal Eye: What does my response reveal about what matters to me now?

Then stop.

Don't answer immediately. Let the questions work on you.

Clarity often emerges sideways—during a walk, in the shower, in a moment of stillness.

Your job isn't to force it. Your job is to notice.

Why Seeing Through Changes Everything

When you develop this perception skill, several things happen.

You stop chasing false urgency. You make fewer but better decisions. You trust your judgment more. You feel less fragmented. You waste less energy explaining yourself.

Life becomes more legible.

Not easier. Clearer.

And clarity, once learned, compounds.

The art of seeing through isn't just for museums or career decisions. It's a way of moving through the world with precision and confidence—because you can read what's actually happening, not just what appears to be happening.

Clarity as a Practice, Not a Destination

The most important thing to understand is this: clarity is not something you achieve once.

It's a way of relating to the world.

A habit of attention. A respect for signals. A willingness to look beneath the obvious.

The three lenses—the Maker's Eye, the Context Eye, the Personal Eye—work everywhere: in museums, in markets, in landscapes you thought you already knew. In the turning points where decision clarity matters most.

Once you develop this capacity, you carry it with you.

An Invitation

If you're at a point where something feels unresolved—not chaotic, just unclear—you may not need advice or strategy.

You may need help seeing what's already there.

I offer private Clarity Sessions for people at turning points who want to understand their situation with precision and depth. These aren't coaching sessions. They're focused perception sessions—the same three lenses described here, the art of seeing through applied to your specific moment.

Sometimes one conversation is enough to restore clarity.

Because clarity was never missing. It was simply waiting to be seen.

Subscribe for essays that change how you see.